Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis, also known as degenerative joint disease (DJD), is the most common type of arthritis. Osteoarthritis is more likely to develop as people age. The changes in osteoarthritis usually occur slowly over many years, though there are occasional exceptions. Inflammation and injury to the joint cause bony changes, deterioration of tendons and ligaments and a breakdown of cartilage, resulting in pain, swelling, and deformity of the joint.

There are two main types of osteoarthritis:

- Primary: Most common, generalized, primarily affects the fingers, thumbs, spine, hips, knees, and the great (big) toes

- Secondary: Occurs with a pre-existing joint abnormality, including injury or trauma, such as repetitive or sports-related; inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid, psoriatic, or gout; infectious arthritis; genetic joint disorders, such as Ehlers-Danlos (also known as hypermobility or “double-jointed; congenital joint disorders; or metabolic joint disorders

Table of Contents

Symptoms of Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis symptoms often develop slowly and worsen over time. Signs and symptoms of osteoarthritis include:

- Pain: Affected joints might hurt during or after movement

- Joint Stiffness: Joint stiffness might be most noticeable upon awakening or after being inactive

- Tenderness: Your joint might feel tender when you apply light pressure to or near it

- Loss of flexibility: You might not be able to move your joint through its full range of motion

- Grating sensation: You might feel a grating sensation when you use the joint, and you might hear popping or crackling

- Bone spurs: These extra bits of bone, which feel like hard lumps, can form around the affected joint

- Swelling: This might be caused by soft tissue inflammation around the joint

Causes of Osteoarthritis

Primary osteoarthritis is a heterogeneous disease meaning it has many different causes, it is not only “wear and tear” arthritis. Some contributing factors to Osteoarthritis are modifiable (can be changed) and others are non-modifiable (cannot be changed such as being born with it or now permanent). Age is a contributing factor, although not all older adults develop osteoarthritis and for those who do, not all develop associated pain. As discussed above, there can also be inflammatory and metabolic risks that can increase the incidence of osteoarthritis, particularly in the setting of diabetes and/or elevated cholesterol.

Osteoarthritis can be genetic both as primary such as nodular Osteoarthritis of the hands as well as secondary related to other genetic disorders, such as hypermobility of joints. Inflammatory and infectious arthritis can contribute to the development of secondary osteoarthritis due to chronic inflammation and joint destruction. Previous injuries or traumas including sports-related and repetitive motions can also contribute to osteoarthritis.

Although the exact mechanisms of cartilage loss and bone changes are unknown, advancements have been made in recent years. It is suspected that complex signaling processes, during joint inflammation and defective repair mechanisms in response to injury, gradually wear down cartilage within the joints. Other changes cause the joint to lose mobility and function, resulting in joint pain with activity.

Risk Factors of Osteoarthritis

Factors that can increase your risk of osteoarthritis include:

- Older age: The risk of osteoarthritis increases with age

- Sex: Women are more likely to develop osteoarthritis, though it isn’t clear why

- Obesity: Carrying extra body weight contributes to osteoarthritis in several ways, and the more you weigh, the greater your risk. Increased weight adds stress to weight-bearing joints, such as your hips and knees. Also, fat tissue produces proteins that can cause harmful inflammation in and around your joints

- Joint injuries: Injuries, such as those that occur when playing sports or from an accident, can increase the risk of osteoarthritis. Even injuries that occurred many years ago and seemingly healed can increase your risk of osteoarthritis

- Repeated stress on the joint: If your job or a sport you play places repetitive stress on a joint, that joint might eventually develop osteoarthritis

- Genetics: Some people inherit a tendency to develop osteoarthritis

- Bone deformities: Some people are born with malformed joints or defective cartilage

- Certain metabolic diseases: These include diabetes and a condition in which your body has too much iron (hemochromatosis)

Prevention of Osteoarthritis

By age 65, more than half of us will have X-ray evidence of osteoarthritis, a disease in which the cartilage that covers the ends of the bones at the joints breaks down and bony overgrowth occurs. For many, the result is stiffness and pain in the joint.

Although osteoarthritis (or OA) is more common as we age, it is not an inevitable part of aging. As researchers work to understand the causes of osteoarthritis, they are able to offer advice to help prevent the disease or its progression and lessen its impact on your life.

Here are four steps you can take now to prevent osteoarthritis or its progression.

1: Control Weight

If you are at a healthy weight, maintaining that weight may be the most important thing you can do to prevent osteoarthritis. If you are overweight, losing weight may be your best hedge against the disease.

Obesity is clearly a risk factor for developing osteoarthritis. Data from the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a program of studies designed to assess the health and nutrition of Americans, showed that obese women were nearly four times as likely as non-obese women to have osteoarthritis. The risk for obese men was nearly five times greater than for non-obese men.

Being overweight strains the joints, particularly those that bear the body’s weight such as the knees, hips, and joints of the feet, causing the cartilage to wear away.

Weight loss of at least 5% of body weight may decrease stress on the knees, hips, and lower back. In a study of osteoarthritis in a population in Framingham, Mass., researchers estimated that overweight women who lost 11 pounds or about two body mass index (BMI) points, decreased their risk of osteoarthritis by more than 50%, while a comparable weight gain was associated with an increased risk of later developing knee OA.

If you already have osteoarthritis, losing weight may help improve symptoms.

2: Exercise

If the muscles that run along the front of the thigh are weak, research shows you have an increased risk of painful knee osteoarthritis. Fortunately, even relatively minor increases in the strength of these muscles, the quadriceps, can reduce the risk.

To strengthen quadriceps, Todd P. Stitik, MD, professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School, recommends isometric moves and wall slides. To do these, stand with your back to a wall, with feet shoulder-width apart. Then lean back against the wall, placing your feet out in front of you as far as you comfortably can. Bend at the knees, put your hands on your waist, and slide with your spine, maintaining contact with the wall until you reach a sitting position. (Your knees should not bend more than 90 degrees). Then slowly slide back to your original position. Repeat eight to 10 times.

If fear of joint pain after exercise keeps you from exercising, try using heat and cold on painful joints or take pain relievers. Doing so may make it easier to exercise and stay active. The safest exercises are those that place the least body weight on the joints, such as bicycling, swimming, and other water exercise. Light weight lifting is another option, but if you already have osteoarthritis, first speak with your doctor.

3: Avoid Injuries or Get Them Treated

Suffering a joint injury when you are young predisposes you to osteoarthritis in the same joint when you are older. Injuring a joint as an adult may put the joint at even greater risk. A long-term study of 1,321 graduates of Johns Hopkins Medical School found that people who injured a knee in adolescence or young adulthood were three times more likely to develop osteoarthritis in that knee, compared those who had not suffered an injury. People who injured their knee as an adult had a five times greater risk of osteoarthritis in the joint.

To avoid joint injuries when exercising or playing sports, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases recommends the following:

- Avoid bending knees past 90 degrees when doing half knee bends

- Keep feet as flat as possible during stretches to avoid twisting knees

- When jumping, land with knees bent

- Do warm-up exercises before sports, even less vigorous ones such as golf

- Cool down after vigorous sports

- Wear properly fitting shoes that provide shock absorption and stability

- Exercise on the softest surface available; avoid running on asphalt and concrete

If you have a joint injury, it’s important to get prompt medical treatment and take steps to avoid further damage, such as modifying high-impact movements or using a brace to stabilize the joint.

4: Eat Right

Although no specific diet has been shown to prevent osteoarthritis, certain nutrients have been associated with a reduced risk of the disease or its severity. They include:

Omega-3 fatty acids: These healthy fats reduce joint inflammation, while unhealthy fats can increase it. Good sources of omega-3 fatty acids include fish oil and certain plant/nut oils, including walnut, canola, soybean, flaxseed/linseed, and olive.

Vitamin D. A handful of studies has shown that vitamin D supplements decreased knee pain in people with osteoarthritis. Your body makes most of the vitamin D it needs in response to sunlight. You can get more vitamin D in your diet by eating fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, tuna, sardines, and herring; vitamin D-fortified milk and cereal; and eggs.

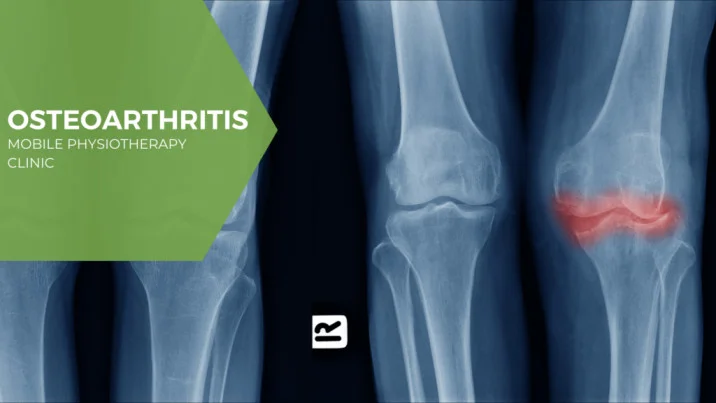

Diagnosis

During the physical exam, your doctor will check your affected joint for tenderness, swelling, redness and flexibility.

Imaging tests

To get pictures of the affected joint, your doctor might recommend:

- X-rays: Cartilage doesn’t show up on X-ray images, but cartilage loss is revealed by a narrowing of the space between the bones in your joint. An X-ray can also show bone spurs around a joint

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): An MRI uses radio waves and a strong magnetic field to produce detailed images of bone and soft tissues, including cartilage. An MRI isn’t commonly needed to diagnose osteoarthritis but can help provide more information in complex cases

Lab tests

Analyzing your blood or joint fluid can help confirm the diagnosis.

- Blood tests: Although there’s no blood test for osteoarthritis, certain tests can help rule out other causes of joint pain, such as rheumatoid arthritis

- Joint fluid analysis: Your doctor might use a needle to draw fluid from an affected joint. The fluid is then tested for inflammation and to determine whether your pain is caused by gout or an infection rather than osteoarthritis

Treatment of Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis can’t be reversed, but treatments can reduce pain and help you move better.

Medications

Medications that can help relieve osteoarthritis symptoms, primarily pain, include:

- Acetaminophen: Acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) has been shown to help some people with osteoarthritis who have mild to moderate pain. Taking more than the recommended dose of acetaminophen can cause liver damage

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Over-the-counter NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve), taken at the recommended doses, typically relieve osteoarthritis pain. Stronger NSAIDs are available by prescription. NSAIDs can cause stomach upset, cardiovascular problems, bleeding problems, and liver and kidney damage. NSAIDs as gels, applied to the skin over the affected joint, have fewer side effects and may relieve pain just as well

- Duloxetine (Cymbalta): Normally used as an antidepressant, this medication is also approved to treat chronic pain, including osteoarthritis pain

Therapy

- Physical therapy: A physical therapist can show you exercises to strengthen the muscles around your joint, increase your flexibility and reduce pain. Regular gentle exercise that you do on your own, such as swimming or walking, can be equally effective

- Occupational therapy: An occupational therapist can help you discover ways to do everyday tasks without putting extra stress on your already painful joint. For instance, a toothbrush with a large grip could make brushing your teeth easier if you have osteoarthritis in your hands. A bench in your shower could help relieve the pain of standing if you have knee osteoarthritis

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS): This uses a low-voltage electrical current to relieve pain. It provides short-term relief for some people with knee and hip osteoarthritis

Surgical and other procedures

If conservative treatments don’t help, you might want to consider procedures such as:

- Cortisone injections: Injections of a corticosteroid into your joint might relieve pain for a few weeks. Your doctor numbs the area around your joint, then places a needle into the space within your joint and injects medication. The number of cortisone injections you can receive each year is generally limited to three or four, because the medication can worsen joint damage over time

- Lubrication injections: Injections of hyaluronic acid might relieve pain by providing some cushioning in your knee, though some research suggests that these injections offer no more relief than a placebo. Hyaluronic acid is similar to a component normally found in your joint fluid

- Realigning bones: If osteoarthritis has damaged one side of your knee more than the other, an osteotomy might be helpful. In a knee osteotomy, a surgeon cuts across the bone either above or below the knee, and then removes or adds a wedge of bone. This shifts your body weight away from the worn-out part of your knee

- Joint replacement: In joint replacement surgery, your surgeon removes your damaged joint surfaces and replaces them with plastic and metal parts. Surgical risks include infections and blood clots. Artificial joints can wear out or come loose and might eventually need to be replaced

Exercises for Osteoarthritis

Gentle stretching exercises can be very helpful if you have OA, especially for stiffness or pain in your knees, hips, or back. Stretching can help improve mobility and range of motion.

As with any exercise plan, check with your doctor before beginning, to make sure it’s the right course of action for you. If stretching exercises get the green light, try these hip exercises.

Natural Remedies for Osteoarthritis

Alternative treatments and supplements may help to relieve symptoms such as inflammation and joint pain. Some supplements or herbs that may help include:

- fish oil

- green tea

- ginger

Other alternative treatment options include:

- acupuncture

- physical therapy

- massage therapy

Other remedies can range from taking Epsom salt baths to using hot or cold compresses.

Talk with your doctor about any herbs or supplements you’re considering before you use them. This will help ensure that they are safe, effective, and won’t interfere with other medications you’re taking.

15 Comments