Zygomatic bone

Table of Contents

Introduction

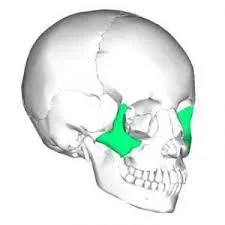

The zygomatic bones are also referred to as the cheekbones. These bones are located directly beneath each eye and extend upward to the outer side of each eye. The zygomatic bones connect to several other facial bones, including the nose, jaw, portions of the eye, and bones just in front of the ears. The zygoma (also known as zygomatic bone or malar bone) is an important facial bone that forms the prominence of the cheek. It is roughly quadrangular in shape.

When a foetus is in utero, the zygomatic bone is cartilage, but it begins to form bone shortly after birth. Underdeveloped zygomatic bones cause significant issues with facial construction due to their size and function in joining many facial bones together. A fracture is the most serious condition associated with the zygomatic bones.

The zygomatic bone also contributes to the formation of the orbital floor and the temporal and infratemporal fossae. Each zygomatic bone connects to four other bones: the maxilla, temporal bone, sphenoid bone, and frontal bone.

There are four margins, three surfaces (orbital, temporal, lateral, or facial), and three processes (frontal, temporal, maxillary, or orbital) on each zygomatic bone. The bone contains the zygomatic canal, which allows the zygomatic nerve and blood vessels to pass through.

Anatomy

The zygomatic bone is rectangular, with portions extending out near the eye sockets and downward near the jaw. The front of the bone is thick and jagged to allow it to connect to other bones in the face. This thickness also allows the bone to remain strong and sturdy to protect the more delicate facial features. Other zygomatic bone joints include those near the jaw, ears, forehead, and skull.

The articulations (where two bones come together) near the skull are not as thick, allowing the skull structure to take over as the main protector of the brain and other underlying structures. There is also a tunnel within the zygomatic bone called the zygomaticofacial foramen, which allows integral veins and arteries to pass through the face.

Variations in Anatomy

The presence of an extra joint dividing the zygomatic bone into two additional sections is one of the anatomical variations of the zygomatic bone. Some people have more than one tunnel within their zygomatic bone, which is known as a zygomatic foramen.

Certain individuals’ zygomatic bones have been found to have multiple landmarks, such as bumps and grooves. Other differences include where the zygomatic bone meets the jaw bone and the forehead, as well as longer landmarks at these joints.

The majority of these variations will not result in the emergence of any medical conditions or concerns. The presence of an additional zygomatic foramen, on the other hand, may be mistaken for an unhealed or disjointed fracture. This may prompt medical personnel to try a delayed treatment for what they believe is a fracture.

Zygomatic arch

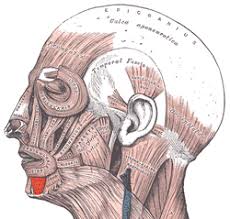

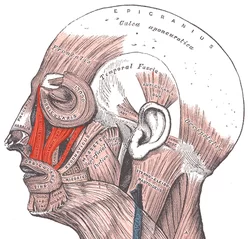

The zygomatic arch is a bone bridge that extends from the temporal bone on the side of the head to the maxilla (upper jawbone) in front, with the zygomatic (cheek) bone playing a significant role. The masseter muscle, which is important in chewing, arises from the arch’s lower edge; the temporalis muscle, which is also important in chewing, passes through the arch. Herbivorous animals, such as baboons and apes, have a particularly large and robust zygomatic arch. The zygomatic arch has become more gracile (slender) as humans have evolved.

For example, Australopithecus robustus, an early hominid, had a large zygomatic arch, which some scholars believe indicates a herbivorous diet, whereas Australopithecus africanus, a later hominid, had a small, fragile-looking arch and is generally thought to have been a hunter and omnivore.

Surfaces of the zygomatic bone

There are three surfaces to the zygomatic bone: lateral, posteromedial, and orbital.

The lateral (facial) surface is exposed to the elements. It is smooth and convex, with a small opening known as the zygomaticofacial foramen. The zygomaticofacial nerve, artery, and vein pass through this foramen between the orbit and the face. The lateral surface also serves as the attachment point for the zygomaticus major and zygomaticus minor muscles on the anterior half and the posterior half, respectively.

The temporal and infratemporal fossae are visible on the posteromedial (temporal) surface. Its anteriormost portion is rough and serves as an articulation point with the maxillary zygomatic (malar) process via the zygomaticomaxillary suture. The posteromedial surface extends over the medial side of the temporal process, forming a portion of the infratemporal fossa’s lateral wall. The zygomaticotemporal foramen, located near the base of the frontal process, transmits the zygomaticotemporal nerve from the orbit to the temporal fossa.

The orbital surface is concave and smooth. It forms the anterolateral part of the floor and the anterior part of the lateral wall and faces the orbit. It has the zygomatic-orbital foramen, which is a portal to the bony canal located within the zygomatic bone. This canal divides into the zygomaticofacial and zygomaticotemporal canals, which open on the corresponding zygomatic bone surfaces (as explained above). The zygomaticofacial nerve and vessels travel through the former, while the zygomaticotemporal nerve and vessels travel through the latter.

Borders of the zygomatic bone

There are five sections to the zygomatic bone:

- The anterosuperior (orbital) border is smooth and concave. It is the zygomatic bone’s border between the lateral and orbital surfaces.

- The anteroinferior (maxillary) border serves as the articular surface for the zygomaticomaxillary suture. It also serves as a site for the levator labii superioris muscle to attach.

- The posterosuperior (temporal) border is continuous with the superior zygomatic arch border and the posterior frontal process border. It acts as a point of attachment for the temporal fascia.

- The posteroinferior border is rough and serves as the masseter muscle attachment site.

- The posteromedial border is serrated and articulates superiorly with the greater wing of the sphenoid bone and inferiorly with the orbital surface of the maxilla via the sphenozygomatic suture. There is a small free surface of the posteromedial margin between the articular surfaces that forms the lateral border of the inferior orbital fissure.

Processes of the zygomatic bone

The zygomatic bone’s temporal process

The temporal process arises from the zygomatic bone’s lower half. It faces the temporal bone posteriorly and slightly superiorly.

The zygomatic process of the temporal bone articulates with the oblique and jagged terminal point of the temporal process to produce the zygomatic arch.

The zygomatic bone’s frontal process

The frontal process arises from the zygomatic bone’s upper margin. It is superiorly oriented and includes the orbit’s lateral outline. The zygomaticofrontal suture connects it to the zygomatic process of the frontal bone superiorly, and the sphenozygomatic suture connects it to the greater wing of the sphenoid bone posteriorly.

Whitnall’s tubercle is a bony tubercle on the orbital surface of the frontal process that serves as an attachment site for the lateral palpebral ligament, suspensory ligament of the eye, as well as the levator palpebrae superioris aponeurosis.

The zygomatic bone’s maxillary process

The maxillary process develops from the zygomatic bone’s anterosuperior angle. It extends anteriorly and includes the orbit’s inferolateral margin. This process’s inferior margin is involved in the joint with the maxilla. In the posterior direction, it is continuous with the bone’s orbital surface.

Function of the zygomatic bone

The zygomatic bone is a structure that connects the bones of the face while protecting the arteries, nerves, veins, and organs beneath the skin. The zygomatic bone arches provide structure to the cheeks, allowing them to fill out the face.

The zygomatic bone cannot move because it is a stationary bone that serves primarily for protection. However, the lower portion of the zygomatic bone that connects to the jaw bone aids in the movement of the jaw bone. This movement allows the mouth to function for a variety of purposes, including facial expressions, speaking, chewing, drinking, coughing, and breathing. The zygomatic bone’s stability allows for motion associated with other bones connected to the zygomatic bone.

Furthermore, the upper zygomatic bone’s grooves and indentations provide space for muscles to insert in the forehead and upper portion of the skull. The zygomatic bone and other facial bones can now connect to the upper portion of the skull.

Associated Disorders of the zygomatic bone

A fracture is the most common condition associated with the zygomatic bone. A fracture to the orbital floor, the portion of the zygomatic bone attached to the eye, also affects the zygomatic bone’s function. A blowout fracture can fracture the zygomatic bone, displace the upper portion of the zygomatic bone that articulates with the skull, and cause a deeper fracture to the eye socket. Jaw fractures can also affect the lower portion of the zygomatic bone, causing difficulty chewing, speaking, and performing other oral functions.

Orbital fractures can cause vision problems as well as muscle spasms in the nearby facial muscles. This is usually the case when there is nerve involvement as a result of a bone fracture.

Rehabilitation

An X-ray is used to diagnose zygomatic bone fractures. Patients are advised not to blow their noses or make any large facial movements that may cause pain or disturb the fracture.5 The zygomatic bone may be monitored at home and treated with antibiotics to prevent or treat infection, depending on the severity of the fracture.

More serious zygomatic fractures can cause eyeball inward displacement, persistent double vision, or cosmetic changes. In these cases, surgery is required to apply fixators to the bones and reduce complications.

In children, the absence of cosmetic changes following a facial injury can lead to a delayed diagnosis. White-eyed blowouts are orbital fractures that occur in children and mimic the symptoms of a concussion. This can include nausea, vomiting, and changes in cognition. In such cases, healthcare providers may treat a concussion while being unaware of the zygomatic and/or orbital bone fracture. If a white-eyed blowout is not treated right away, there is a risk of tissue death, which can lead to infection and other serious complications.

Summary

The zygomatic bones, also known as cheekbones, are located beneath each eye and extend upward to the outer side of each eye. They connect to several other facial bones, including the nose, jaw, portions of the eye, and bones just in front of the ears. The zygoma, an important facial bone, forms the prominence of the cheek. Underdeveloped zygomatic bones cause significant issues with facial construction and are the most serious condition associated with them.

Each zygomatic bone connects to four other bones: the maxilla, temporal bone, sphenoid bone, and frontal bone. The zygomatic bone is rectangular, with portions extending out near the eye sockets and downward near the jaw. Its thickness allows it to remain strong and sturdy to protect delicate facial features. Variations in anatomical variations include the presence of an extra joint dividing the zygomatic bone into two additional sections, multiple landmarks, and longer landmarks at joints. The zygomatic arch is a bone bridge that extends from the temporal bone to the maxilla.

The zygomatic bone is a stationary structure that connects face bones, protecting arteries, nerves, veins, and organs. Its stability allows for movement and allows for facial expressions, speaking, chewing, drinking, coughing, and breathing. Associated disorders include fractures, blowout fractures, and orbital floor fractures. Rehabilitation involves X-ray diagnosis, antibiotic treatment, and surgery for more severe cases. White-eyed blowouts in children can delay diagnosis and cause complications.

FAQs

The zygomatic bone (zygoma) is an irregularly shaped skull bone. It is the prominence just below the lateral side of the orbit that is commonly referred to as the cheekbone. The zygomatic bone has three surfaces, five borders, and two processes and is nearly quadrangular in shape.

The zygomatic bone is also known as the cheekbone. It is also known as the malar bone. This bone forms the most visible part of the cheek and is paired, appearing on both the right and left sides of the nose.

The anatomy of the zygomatic bone is not overly complicated; its main function is to provide structure and strength to the mid-face. There are three surfaces, four processes, three foramina, and three articulations on the cheekbones. Processes are bone fragments that project into other bones.

Each zygomatic bone is diamond-shaped and composed of three processes with associated bony articulations that are also named similarly: frontal, temporal, and maxillary. Each process of the zygomatic bone contributes to the formation of important skull structures.

Herbivorous animals, such as baboons and apes, have a particularly large and robust zygomatic arch. The zygomatic arch has become more gracile (slender) as humans have evolved.

References:

- Vasković, J. (2023, November 3). Zygomatic bone. Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/the-zygomatic-bone

- Ferri, B. (2022, April 22). The Anatomy of the Zygomatic Bone. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/zygomatic-bone-anatomy-4692051

- Zygomatic bone | Facial Structure, Cheekbone & Maxilla. (2023, November 30). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/zygomatic-bone

- Hacking, C., & Batta, N. (2016, July 17). Zygoma. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rid-46790

- Next, A. (n.d.). %s | Anatomy.app | Learn anatomy | 3D models, articles, and quizzes. https://anatomy.app/encyclopedia/zygomatic-bone