What is the Mckenzie Method of Physical Therapy?

The McKenzie technique of physical therapy, sometimes known as MDT (mechanical diagnostic and therapy), is a way of diagnosing and treating musculoskeletal disorders of the spine and extremities.

The McKenzie method of exercise was developed by Robin McKenzie(1931-2013) in 1981, a physical therapist from New Zealand. The feature of the method emphasizes patient empowerment and self-treatment.

MDT characterizes patients’ complaints with clinical presentation. The classification has been confirmed by many researchers.

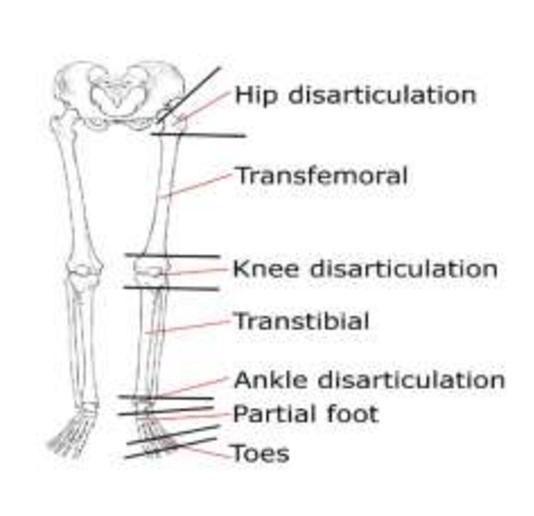

In the treatment by the McKenzie method disorders in the spine, with symptoms in the extremities, an important place takes Centralization- the symptoms movement from the distal segment of the body to the proximal.

The onset of centralization is a positive indication that the right steps are being taken; in contrast, peripheralization, or the pain radiating from the extremities down the spine, is making the condition worse.

Table of Contents

The Mckenzie method includes 4 steps:

1. Assessment:

First taking a history of symptoms and behavior. After that perform certain movements and take specific positions. Ask for symptoms of affection. The symptoms and range of movements change with these repeated movements and positions providing the therapist with information that is used to be aware of the nature of the problem.

2. Classification:

Derangement syndrome, dysfunction syndrome, and postural syndrome McKenzie’s method is based on the direction (Flexion, extension, or lateral shift of the spine).

3. Treatment:

The initial step in treatment is to identify a prolonged or repeated movement that lessens or eliminates the symptoms. The next objective is to sustain this progress for a few days. In order to assess whether they are pain-free at this point, the patient conducts recovery of function, which involves having them do once-painful activities.

4. Prevention:

The patient is instructed and encouraged to exercise regularly and practice self-care as part of the preventative stage.

Usually, the exercise prescribed is focused on a single direction, determined by the presenting symptoms. Depending on what happens with the symptoms, the exercise may involve repeated motions or maintained positions.

It may also call for reaching the end or occasionally the mid-range of motion. All distal referred symptoms eventually disappear when one performs repetitive motions or maintains a particular posture, and any residual spinal pain also goes away.

Research indicates that although this approach might not be more effective than alternative rehabilitation interventions in terms of reducing pain and disability in individuals with acute lower back pain, there is a moderate to high degree of evidence indicating that MDT is superior to other approaches in terms of reducing both in patients with chronic lower back pain.

According to a recent study, MDT is a successful treatment to reduce pain in the short term and improve function in the long run when compared to manual therapy in the management of patients with chronic lower back pain. According to one study, persons with a forward head posture had substantially better cervical posture.

Classification

Based on their mechanical and symptomatic reactions to repeated movements and/or prolonged postures, patients are divided into four groups. It is not always the case that classifications are provided during the initial evaluation; in certain instances, confirmation of a classification may need three to five visits.

When using this strategy, keep in mind the key concepts presented in the 4-minute video below.

Every syndrome requires a unique method of management.

The four MDT classification types and their descriptions are listed below.

Derangement Syndrome

- This syndrome is increasingly prevalent and well-known.

- One of this syndrome’s main characteristics is change and inconsistency.

- It is possible for symptoms to be local, referred, radicular, or a combination of these. They may also shift from proximal to distal or side to side.

- The symptoms may be ongoing, intermittent, or change during the day.

- The onset may occur gradually over time or suddenly with no apparent cause.

- Postures and routine everyday activities may have an impact on the symptoms.

- A distinguishing feature of derangement syndrome is directional preference, wherein a certain repetitive movement or prolonged posture results in a meaningful improvement of symptoms.

- Specific movements that reduce, centralize, or eliminate pain are part of the treatment.

Dysfunction Syndrome

- Refers to pain that arises from the mechanical deformation of tissues that are structurally compromised, such as adhering or shorter tissue that is adaptable.

- The symptoms have to last for eight to twelve weeks in order for the tissues to deteriorate.

- At the end of a limited range of motion, there is always intermittent pain.

- Repetitive motions in the direction of the malfunction or the direction that causes the discomfort are part of the treatment. The goal is to use workouts to restructure that tissue, which restricts movement until it eventually becomes pain-free.

Postural Syndrome

- Refers to pain that results from prolonged end-range stress of periarticular structures, which mechanically expands normal soft tissue.

- The pain occurs when the spine is immobile, such as when sitting with a prolonged slouched posture.

- When the patient is moved from the immobile position, the pain goes away.

- Performing an activity or movement hurts no discomfort.

- Patient education, posture correction through the restoration of lumbar lordosis, avoidance of provocative postures, and prevention of extended tensile stress on normal structure are all part of the therapy plan.

Other or non-mechanical Syndrome

Some patients exhibit symptoms and signs of additional illnesses but do not fit into any of the three mechanical syndromes. Verifying a classification may need three to five visits to make sure all forces and planes have been used.

- Spinal Canal Stenosis

- Hip disorders

- Sacroiliac disorders

- Low back pain in pregnancy

- Chronic pain syndrome

- Mechanically inconclusive

- Mechanically unresponsive radiculopathy

- Structurally compromised

- Post-surgical problems

- Trauma/Recovering trauma

A patient’s classification as “Other” does not exclude them from changing in the future. The choice of treatment is frequently influenced by time.

Strong inter-rater reliability is demonstrated by this classification among physiotherapists with MDT training.

Treatment

MDT exercises are designed to directly reduce or even completely remove the patient’s symptoms, in contrast to traditional low back pain exercises that focus on muscular strengthening, stability, and range of motion restoration.

By offering a correcting mechanical directional movement, this effect is achieved. Studies have demonstrated improvements in lumbar pain in those with a preference for certain directions.

Patients are instructed by MDT how to move and position themselves to minimize pain. This method uses a cautious progression of repeated pressures and loads. The workouts could hurt at first, but the symptoms will go away after a few repetitions.

Exercise Force Progression

It can be necessary to apply force progression in order to achieve the expected outcomes. The patient’s symptoms will determine which progression is used.

- Static: Mid Range – Static End Range

- Dynamic: Mid Range – End Range – Self Overpressure

- Clinician Generated: Patient to End Range – Overpressure – Therapist mobilization – Manipulation

Exercise Prescription

The patient’s response to the clinician determines what exercises should be prescribed. An example of a prescription that was provided to a patient based on a positive response during a treatment session is as follows.

- 10. repetitions of the movement per 2 hours

- Take motion to end range

- Postural awareness

- In the next 24 to 48 hours, follow up to evaluate progress

The physician will evaluate the patient’s initial symptoms and reaction to the prescribed exercise/activity during the follow-up visit. Often, the patient’s prescribed activities are left unchanged if they return and show great improvement. Force progressions or other options may be investigated if the patient returns in the same manner. Reevaluate the patient if they return worse.

Examples of Common MDT Exercises

These are typical exercises or motions that are used to address the symptoms of lumbar pain in patients. The evaluation and the patient’s clinical response are taken into consideration while choosing a movement. The way the symptoms react to a particular workout or activity both during and after it is performed informs the choice of exercises or motions.

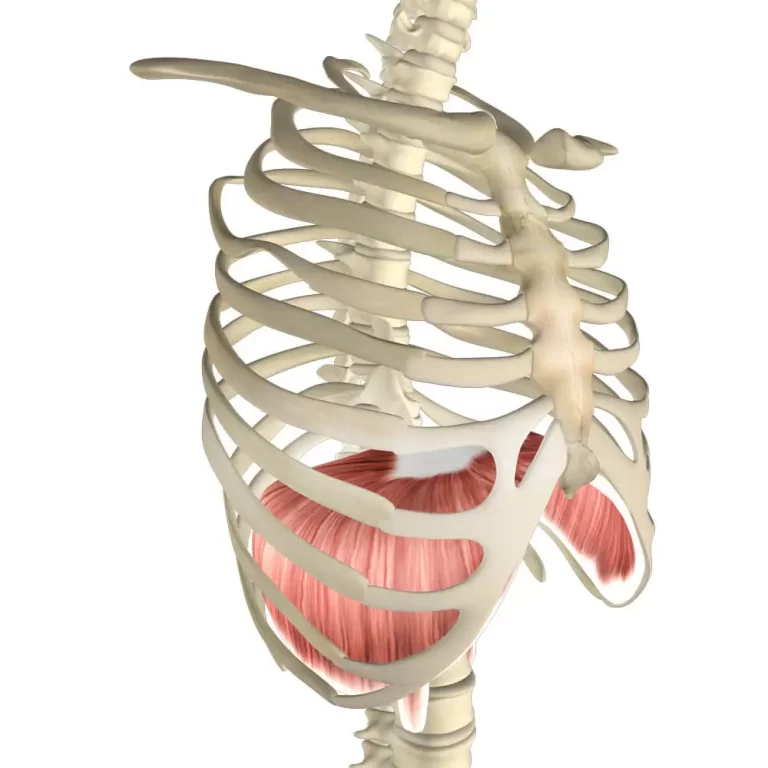

Lying Prone

For people who are acutely pain sensitive, this simple exercise can be quite beneficial. With their head tilted to one side or the other, the patient lies on their stomach. The lumbar spine may become lordosed in this position. To ascertain the cause of the symptoms, the patient stays in this posture for a minimum of three minutes. In extreme circumstances, this position may frequently be sufficient to cause a reduction in symptoms, enabling the patient to advance to repeated or sustained motions.

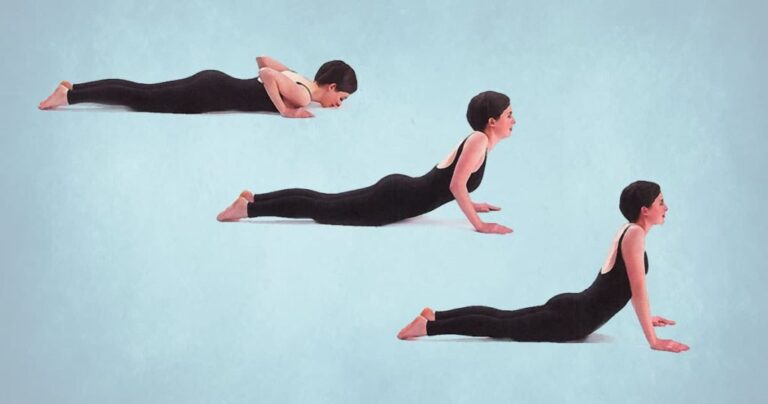

Extension in Lying

With their hands close to their shoulders, the patient is lying on their stomach, seemingly prepared to attempt a push-up. The patient then keeps their hips and knees on the table while pressing their shoulders up toward the ceiling. The objective is to extend to the farthest extent possible before returning to the table; however, this motion may be restricted because of heightened pain or an obstruction. The patient goes back to the table if this is the case. Ten repetitions are usually done at a steady, regular pace. As you listen to the symptoms, attempt to push yourself farther toward the end range each time.

As many times as necessary, repeat the exercise if the symptoms are lessening, centralizing, or disappearing. When it comes to treating derangement and extension dysfunction, this technique is the most significant and successful.

Modifications to Prone Extensions:

- While the patient extends, the therapist adds PA pressure.

- As the patient extends, the therapist moves the spine.

- Start from the side of the hip that hurts and move your hips off-center. Repeat press-ups ten to fifteen times.

- Similar to before, but with iliac rest and ribs experiencing lateral overpressure.

Extension in Standing

This is a standing exercise that is comparable to the laying extension exercise. This procedure may be used if the patient is unable to tolerate lying on their stomach or if lying longer than usual exacerbates their pain. To maintain a steady posture, the patient stands up straight with their feet apart. The hands are positioned in the vicinity of the posterior superior iliac spine on the lumbar region. As the patient leans back, his hands fixate the pelvis. The patient must recline as much as possible.

Ten repetitions of this exercise are required. Lean the patient against a strong desk or cupboard if balance is a problem or if they require additional extension. Depending on the clinical response, it may have consequences on derangement and dysfunction that are comparable to extension in lying.