Zygomatic Fracture

Table of Contents

Introduction

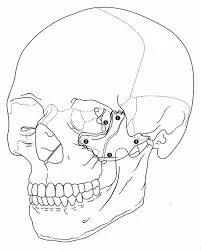

Following nasal bone fractures, zygomatic fractures are the second most common face fractures, occurring primarily in males in their twenties and thirties. The zygomatic bone, particularly the malar eminence, influences the appearance of our faces. It is a component of the orbit’s lateral wall and floor, as well as the zygomatic arch. It also has tiny holes, known as foramina, that allow important neurovascular structures to pass through.

The zygomaticotemporal and zygomaticofacial arteries, as well as nerves, pass through the zygomatic bone foramina. These provide sensory innervation to the anterior temple and cheeks. The zygomatic arch is an important bone for the attachments of structures such as the temporalis fascia and the masseter muscle origin. The Whitnall tubercle, which is also located on the zygomatic bone, is the point of attachment for the tendons of the lateral canthi of the eyelids and is essential for maintaining the contour of the lids.

Etiopathogenesis

Kinetic force is required for a fracture to occur in the zygomatic bone. The force of the impact is directly proportional to the severity of the injury. As a buttress between the skull and the maxilla, the zygomatic bone is quite strong. However, because of its prominence, it is particularly vulnerable to injury, especially when struck on either side of the face. Violent altercation is the most common cause of zygomatic fractures. Then comes the motor vehicle accident (MVA). These fractures can also occur as a result of falls or activities like cycling or skiing.

Fractures in the zygomatic bone can occur along suture lines such as the zygomaticofrontal, zygomaticotemporal, and zygomaticomaxillary. Furthermore, the fracture lines can extend through the zygomatic bone’s articulation with the sphenoid bone’s greater wing. Forces ranging from mild to moderate may result in non-displaced fractures. This means that the bone may have a crack, but its alignment is unaffected. Forces from higher energy impacts, on the other hand, may cause displacement, whereas significantly higher forces, such as those from an MVA, may result in comminuted fractures. This is the bone splintering into multiple fragments.

Classification of Zygomatic Fracture

To aid in their management, several classification systems have been used to describe zygomatic fractures. Knight and North’s 1961 classification system is based on six distinct groups of zygomatic fractures. Group I fractures are those that do not cause significant displacement of the zygomatic bone.

Fractures with isolated displacement are classified as group II, whereas un-rotated (i.e. displaced bodies) fractures are classified as group III. Medially and laterally rotated fractures are classified as Group IV and V, respectively. Group VI fractures occur when there is an additional fractured line within the main fragment.

The Manson classification system, a more modern classification system, uses CT scans to assess zygomatic fractures. The Manson classification system divides zygomatic fractures into three types: low, medium, and high-energy zygomatic fractures. Low-energy fractures are those that do not cause bone displacement. Middle-energy fractures can reduce displacement and, in some cases, comminution. High-energy fractures have significant displacement and comminution.

Henderson, Ellis, Zing, Larson and Thompson, and Rowe and Killey classifications are among others. None of the systems is universally accepted, and the majority of them are based on the location of the fracture as well as the degree of comminution and displacement, whether inferior, medical, or posterior.

Signs and Symptoms of zygomatic fracture

Symptoms of zygomatic fractures include:

- Ecchymosis/haematoma/bruising around the eyes

- Epistaxis

- Subconjunctival hematoma

- Diplopia

- En/Exophthalmos

- Paraesthesia or infra-orbital anaesthesia

- Deformity

- Mandibular movement restrictions (if the TMJ is restricted due to a fractured zygomatic arch)

- Emphysema of the subcutaneous layer

Diagnosis of zygomatic fracture

A radiographic evaluation of the fracture is required, which may include plain films as well as a computed tomographic (CT) scan. CT scans have largely replaced plain films as the gold standard in both evaluation and treatment planning.

If the physical findings and plain films do not indicate a zygomatic fracture, the evaluation may be terminated here. A coronal and axial CT scan should be obtained if they do suggest fracture. The CT scan will accurately reveal the extent of orbital involvement as well as the degree of fracture displacement. This research is critical for developing an operational strategy.

Treatment of zygomatic fracture

Patients involved in traumatic accidents are treated using the advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocol. This protocol evaluates the airway, breathing, and circulation while taking the necessary steps to ensure their proper maintenance.

The Glasgow coma scale is used to evaluate the patient’s mental status, and a neurological examination is performed if necessary. Furthermore, areas of interest are exposed for physical exploration so that important details that could affect the prognosis are not overlooked. Analgesics are used to manage pain, while antibiotics are used to treat open wound fractures. The patient is provided with a tetanus shot whenever required.

The goal of treating a zygomatic fracture is to restore normal or near-normal functionality. This includes restoring normal somatosensory and masticatory function, as well as facial cosmetic features.

Surgical intervention isn’t always required. This is especially true for zygomatic fractures that are stable and non-displaced and require only simple observation during healing. Surgery, if necessary, is performed within three weeks of the injury and involves closed or open reduction, as well as plate and screw fixation. In general, the prognosis is favourable.

Medical Treatment

Zygomatic fractures are usually visible when fracture segments have little or no displacement. Additionally, if other comorbidities preclude safe surgery, medical management may be the best option. Although there is no strong evidence to support the use of prophylactic antibiotics in upper and midface fractures, some surgeons prescribe a 5- to 7-day course of antibiotics, especially if there is communication with the maxillary sinus. Antibiotics should cover sinonasal flora if prescribed.

Surgical Intervention Description

In general anaesthesia, zygomatic complex fractures were surgically treated with oral or nasotracheal intubation. Different surgeons performed the surgical intervention using a similar surgical technique. To begin, an ocular motility forced duction test was performed to determine the presence or absence of extraocular muscle entrapment.

An upper buccal vestibular incision was made from the canine to the first molar after local anaesthesia. Reflection of the mucoperiosteum revealed the nasomaxillary and zygomaticomaxillary buttresses. The infraorbital nerve was discovered and safeguarded. Rowe’s elevator was used to elevate and manipulate the depressed zygomatic complex into its proper anatomical alignment under direct vision, while the contour of the infraorbital rim and the frontozygomatic junction were palpated.

Even when the fracture reduction was stable and the anatomic alignment was adequate, the zygomatic complex fracture was almost always stabilized with mini-plate fixation at the zygomaticomaxillary buttress.

If the fracture reduction was insufficiently anatomically aligned or the zygomatic complex was deemed unstable, the zygomaticofrontal junction and/or infraorbital rim were exposed for second or third fixation points. Finally, an ocular motility forced duction test was performed to determine the presence or absence of extraocular muscle entrapment. Absorbable sutures were used to close the sulcus incision, and extraoral closure was done in layers with Vicryl 4-0 and Prolene 5-0 sutures.

Complications of zygomatic fracture

Poor zygomatic fracture reduction and fixation will result in several functional and aesthetic complications, the most troubling of which is the persistence of diplopia. Other potential functional deficits include limited mouth opening and lower eyelid retraction.

Malar flattening, orbital dystopia, and enophthalmos are common aesthetic sequelae. To avoid these postoperative complications, great care should be taken in the primary management of these fractures to achieve proper alignment and fixation.

Rehabilitation and Postoperative Care

Postoperative care and recovery differ depending on the severity of the injury and the subsequent repair methods used. In any case, the patient should be advised to avoid strenuous activity for at least two weeks to allow for complete healing with minimal bruising and swelling.

Postoperative ancillary care may include lubricating eye drops (orbital fractures), nasal irrigations (communication with sinonasal contents), oral rinses (intraoral incisions used), or a soft diet (mandible fractures/malocclusion). Incision lines require antibiotic ointment application (ophthalmic ointment for periorbital incisions) for at least 72 hours after surgery, followed by petroleum ointment application until the incisions heal completely.

Sun protection and/or avoidance of sun exposure, as well as the use of silicone-based scar creams/ointments, may help improve the appearance of any scars. The patient should be closely monitored postoperatively for any potential complications, specifically infection and/or visual complaints. Visits are usually scheduled one week after surgery and then every few weeks until the fractures appear stable and any complications are ruled out.

Summary

Zygomatic fractures are the second most common face fractures, primarily in males in their twenties and thirties. They are a component of the orbit’s lateral wall and floor, as well as the zygomatic arch. The zygomatic bone is a key component for the attachment of structures such as the temporalis fascia and the masseter muscle origin. The zygomatic bone is vulnerable to injury due to its prominence, making it susceptible to violent altercation and motor vehicle accidents.

Several classification systems have been used to describe zygomatic fractures, including Knight and North’s 1961 classification system, the Manson classification system, Henderson, Ellis, Zing, Larson and Thompson, and Rowe and Killey classifications.

Clinical presentation of zygomatic fractures include pain, limitations in movements, and potential bleeding. Treatment involves the advanced trauma life support protocol, Glasgow coma scale, neurological examination, analgesics, and antibiotics. The goal is to restore normal functionality, including somatosensory and masticatory function, and facial cosmetic features. Surgical intervention typically involves oral or nasotracheal intubation, to restore normal functionality.

Poor zygomatic fracture reduction can lead to functional and aesthetic complications, such as diplopia, limited mouth opening, and lower eyelid retraction. Postoperative care includes avoiding strenuous activity, ancillary care, antibiotic ointment, sun protection, and silicone-based scar creams.

FAQs

Fractures of the ZMC or zygomatic arch can frequently result in unsightly malar depression, which should be corrected to restore a normal facial contour. ZMC fractures can also cause significant functional issues, such as trismus, enophthalmos, and/or diplopia, and infraorbital nerve paresthesias.

In 70% of patients, zygomatic bone fractures cause pain on palpation. There may be paresthesias in the distribution of the infraorbital, zygomaticofacial, or zygomaticotemporal nerves. Posterior displacement of the fracture fragment may impinge on mandibular movement, causing mastication difficulty.

Paresthesias in the distribution of the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve, trismus, diplopia, and zygoma flattening are symptoms of ZMC fracture. Subconjunctival and periorbital haemorrhage, as well as hypesthesias in the distribution of the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve, are classic symptoms.

Most surgeons recommend surgical intervention before dense scar tissue forms. As a general rule, surgery should be performed within three weeks of the injury. Historically, closed-reduction techniques were the preferred method for nearly all zygomatic fractures.

The Gilles temporal approach has long been a popular surgical technique for reducing zygomatic complex fractures. However, this surgical approach is associated with a hairline facial scar and the risk of facial nerve palsy.

References

- Bergeron, J. M. (2022, June 27). Zygomatic Arch Fracture. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549898/

- Zygomatic Fractures. (2019, February 27). News-Medical.net. https://www.news-medical.net/health/Zygomatic-Fractures.aspx

- World Rugby Passport – Zygomatic fractures. (n.d.). https://passport.world.rugby/player-welfare-medical/immediate-care-in-rugby/facial-injuries-in-sport/hard-tissue/zygomatic-fractures/

- Zygomatic Fractures. (n.d.). https://www.sargentcraniofacial.com/procedures/Zygomatic-Fractures

- Zygomatic Fractures. (2013, February 18). American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/education/current-insight/zygomatic-fractures